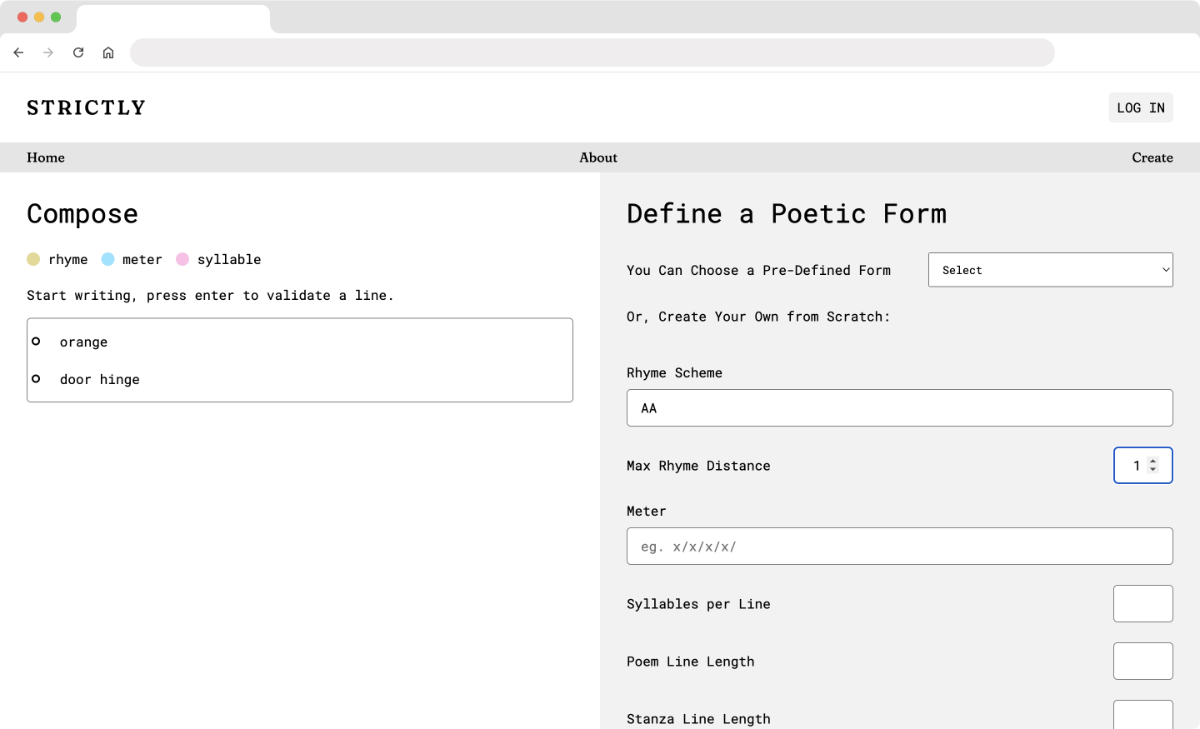

A rhyme & meter checker built for poets.

The seed for this project was a vision of a platform for users to collaborate on poems in strictly defined meters. I was thinking of renga, a Japanese collaborative poetry form.1 I was also imagining the absurdity of a "social media" platform that would require users to post in, e.g., rhyming couplets.

This is the fulfillment of the first stage of that vision: an online rhyme and meter checker. I wanted it to be a tool that embraced how poets actually treat the restrictions of poetic form—not as divine laws that must be precisely followed, but as a musculo-skeletal architecture that can be tensed and relaxed at will. That is, I wanted it be capable of looseness. To embrace deviations.

Rhyme¶

When people talk about rhyme they usually mean "perfect rhyme"—

- boss, toss

- pulley, bully

Perfect rhyme is boring and malicious. It pushes soulless pedants to say things like "nothing rhymes with orange". Rhyme is one of our elemental tools of linguistic expression, and perfect rhyme flattens it into a pompous child's play-thing.

So, for this Rhyme Checker I didn't want to ask "do these words rhyme?" I wanted, instead, a measure of distance between pronunciations. Set a distance of zero, and yes, OK, perfect rhyme—but widen the rhyme-aperture and you get to behold the rhyme between "orange" and "door hinge" in all of its glory.

Step One: Vowels¶

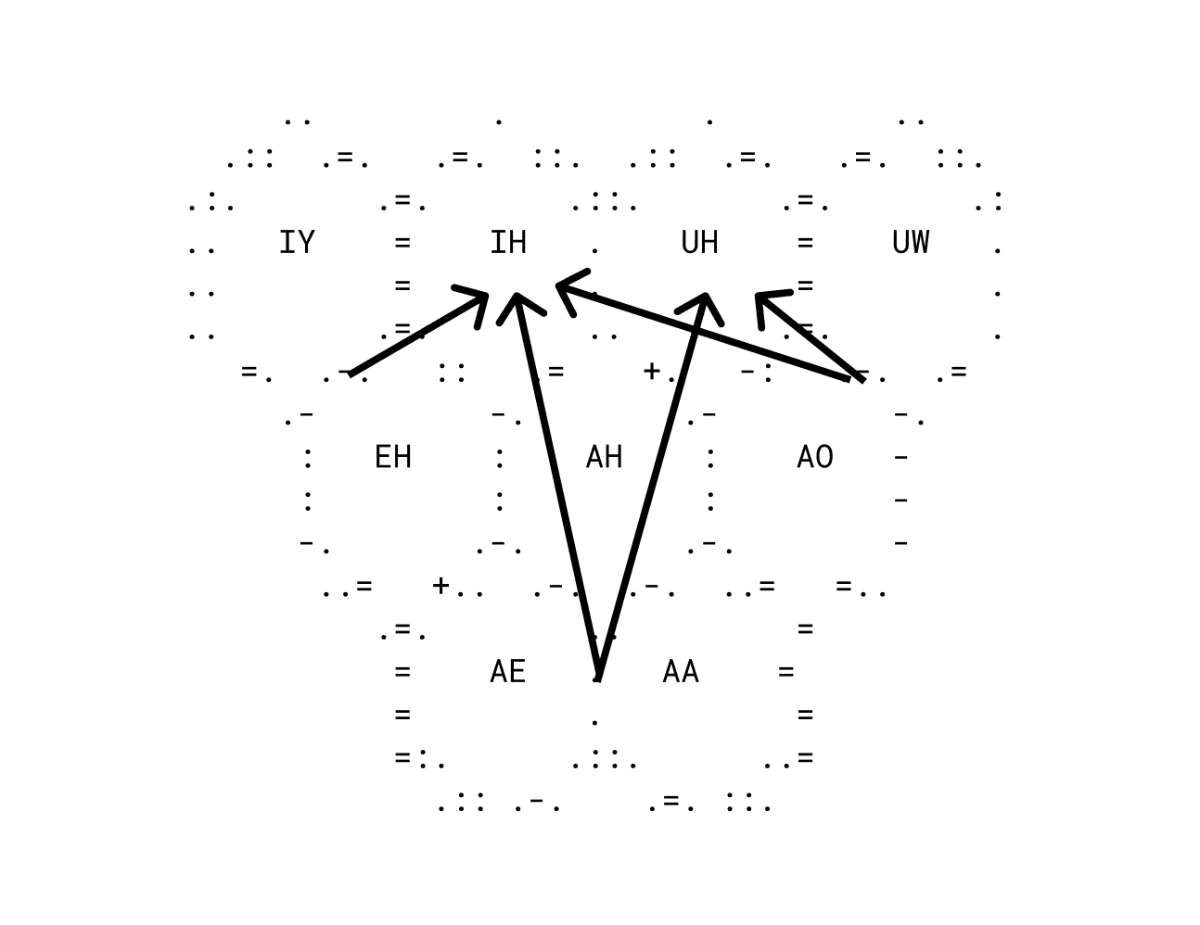

The first step was to find a measure of distance between vowels.

Vowels can be mapped into a 2-D space, where the axes are the first and second formant frequencies. This observation might lead one to the natural thought of using Euclidean Distance to measure vowel distance. I think this could work. But there are complications that made me want to avoid it. My primary concern is that—while vowel space is continuous—perceptually, vowels are discrete. What matters is not the distance between vowels, but the difference between vowels.2

I wanted a system for measuring distance that was based in adjacency. Thus was born the Vowel Hex Graph.

Vowel Hex Graph¶

The vowels used in the CMU Pronouncing Dictionary can be arranged into a hexagonal grid, as if that was how they were always meant to be arranged.4 It is a perfect abstraction, whose beauty seems to be evidence of its truth. Distance could thus be measured by means of counting the number of tiles borders one would have to cross to get from one vowel to another. Life would be lovely and everything would make perfect sense. Until, that is, one remembered the diphthong problem.

.. . . ..

.:: .=. .=. ::. .:: .=. .=. ::.

.:. .=. .::. .=. .:

.. IY = IH . UH = UW .

.. = . = .

.. .=. .. .=. .

=. .-. :: .= +. -: .-. .=

.- -. .- -.

: EH : AH : AO -

: : : -

-. .-. .-. -

..= +.. .-. .-. ..= =..

.=. .. =

= AE . AA =

= . =

=:. .::. ..=

.:: .-. .=. ::.

The Diphthong Problem¶

Some vowels are not just points in vowel space. What we call diphthongs are a movement between two points in vowel space. For example, the vowel in "boy"—if you slow down your pronunciation you can hear the sound of "oy" moving from a vowel near "oh" to a vowel near "ee".

This raises the thorny problem of what exactly we mean by "the distance between" a single-point vowel (called a monophthong) and a diphthong. Do we measure from the starting point of the diphthong? The ending point? From the closest point to the vowel we're measuring it against?

Or should we not treat a diphthong as a vowel at all, but as in fact two separate vowels? This seems attractively rigorous, but it doesn't seem to track with how English-speakers typically conceive of vowels?

What I did instead is that I sat down, muttering the vowel sounds to myself, and constructing on top of the perfect abstract edifice of the Vowel Hex Graph, an arbitrary / idiosyncratic maze of adjacencies.

1. AW as in BOUT is adjacent to:

UH as in BUSH

OW as in BOAT

AH as in BUT

2. AY as in BITE is adjacent to:

IH as in BIT

EY as in BAIT

AH as in BUT

Etc. etc. for all five major English diphthongs.

Vowel Distance¶

Once we have a full graph of vowel adjacencies, we do a Breadth-First Search to find the shortest distance between them.

This was my first graph algorithm, very cool.

Step Two: Consonants¶

The next step is to find the distance between consonants. One thing to note is that, unlike vowels, consonants are discrete: you can not move smoothly from one to another. Consonants can be classified according to these three dimensions:

- Where the constriction is made in the mouth (e.g., at the lips, against the roof of the mouth, etc.)

- How much the flow of air is constricted (e.g., a complete blockage of the flow of air, as in p, or only a partial blockage, as in s)

- Whether or not the sound involves "voicing"

These are referred to as 1) place of articulation, 2) manner of articulation, and 3) phonation. I referred to this chart, which organizes all of the IPA pulmonic consonants according to these three dimension. I made a new version of it, containing only the consonants used in the CMU dictionary. And then I spent some time thinking through the relationships I observed.

Observations¶

- Place of Articulation is relevant for sorting similarity between consonants that share a Manner of Articulation, not across Manners.

- Place Of Articulation can be arranged into a linear dimension. That is, the eight "places" of consonants in the CMU dict can each be assigned a number 1-8, with roughly equal pronunciation distances between each number.5

- Within a group of consonants that share a Manner of Articulation, the difference between a voiced and unvoiced consonant with the same Place of Articulation is approximate the same as the difference between two consonants whose Place of Articulation is .

Using these observations, I wrote a function for calculating consonant distance.

Step Three: Distance¶

Now we want to find the distance between two entire words. First we convert them to IPA, using the CMU Pronouncing Dictionary. This gives us two strings of phonemes that we want to find the distance between.

My first thought was to use Levenshtein distance which is "the minimum number of single-character edits (insertions, deletions or substitutions) required to change one word into the other". But I wanted to be able to match up vowels-to-vowels and consonants-to-consonants, and, at first glance, Levenshtein distance didn't seem to offer a means to do this.

So I went searching. Who has spent a lot of time thinking about ways of calculating distance between strings? Answer: biologists.

Bioinformatics¶

Biologists want to be able to align strings. In their case these strings are amino acid or nucleotide sequences. But the idea is roughly the same.

[To Be Continued...]

Renga would give birth to the much better known haiku when the renga's starting stanza, the hokku, was severed from the rest of the poem.

For example, consider the vowel sounds in "bat", "bet", and "bot".

Using some reasonable average frequencies of F1 and F2 for a male voice we would get Euclidean distances of:

bat -> bet: 191.64 bat -> bot: 787.48But the vowels in "bet" and "bot" are each—in, I think, a meaningful sense—"adjacent" to the vowel in "bat": one can move thru vowel space from one to the other without passing thru another vowel. Euclidean distance suggests a difference that I don't think is perceptually relevant.3

One reason for the discrepancy in the distances is that they are moving along different axes from "bat"—"bet" along the F1 axis, and "bot" along the F2 axis. We could try to correct for this discrepancy by scaling the axes. But it's not obvious that this give us what we actually wanted—or if it would be an quantitative kludge standing in for a lack of metaphysical foundation.

The one exception here is /W/ which is really a weird gliding semi-vowel.