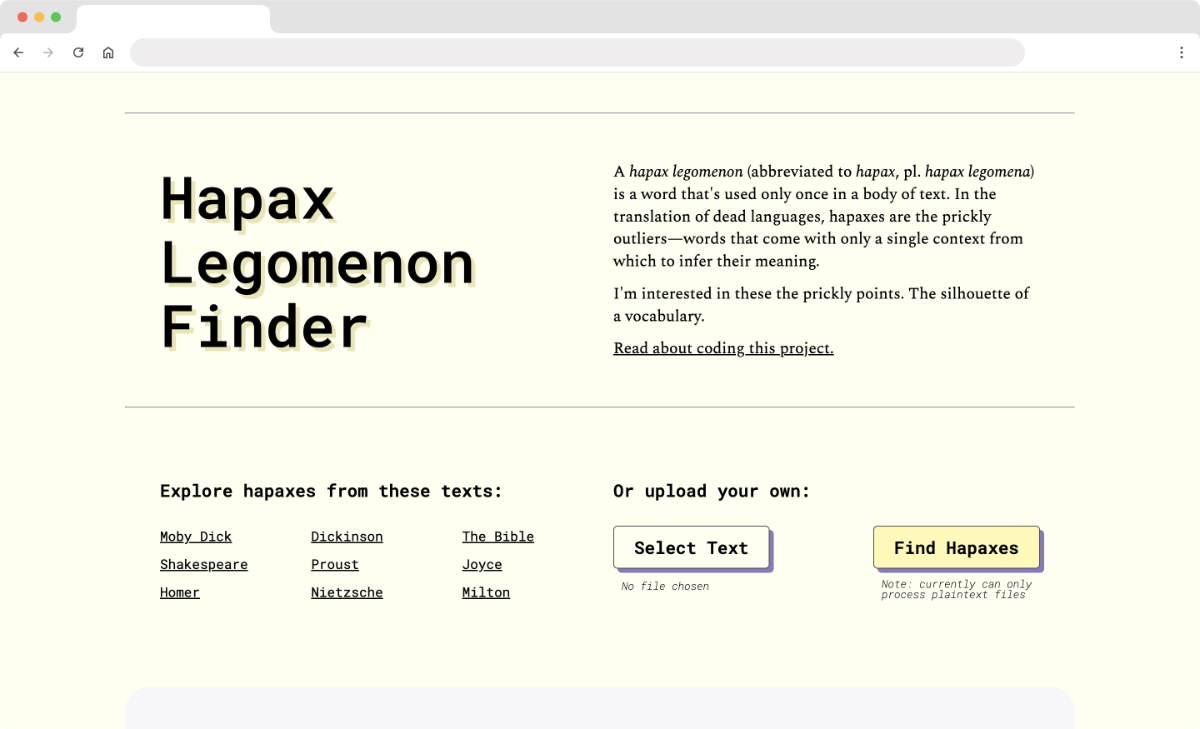

Find hapaxes from the safety of your home.

Coding the Finder¶

A hapax legomenon (abbreviated to hapax, pl. hapax legomena) is a word that's used only once in a body of text. The term comes from the study of ancient texts. Hapax legomena are the prickly outliers of translation—words that come to us with only a single context from which we can try to infer their meanings.

I'm interested in these prickly points. The silhouette of a vocabulary.

I'd been studying C++ for a few weeks, and a hapax finder seemed like a project I could achieve. The steps were fairly simple:

- Open the text file.

- Read thru the file word-by-word.

- Check if you've already come across this word.

- If you have, increment the count of times you've seen the word.

- If you haven't, add the word with a count of one.

- Once you've read thru the entire text, spit out all the words with a word-count of one.

I knew I wanted to use a hashmap to store the words and word-counts, for quick access to each word, but I was so new to C++ that I didn't realize the standard library came with it's own hashmap container, std::unordered_map. Instead, I implemented my own hashmap, using the MurmurHash2 algorithm to hash each word, and place it in an array of linked-lists. Glad to know I can roll my own hashmap—it might be an important skill in a post-apocalyptic world.

The trickiest part was dealing with punctuation. The algorithm would read in each word until it encountered whitespace, including whatever punctuation clung to the word. So I needed to strip away the punctuation, but I also wanted to include compound words, with an internal dash—e.g. "half-unhinged". And—one last wrinkle—if the algorithm read in, e.g. "wrinkle—if", it needed to know that those were two words that it should record separately.

Ok, easy enough—I crafted a regular expression to match all the sorts of words I wanted, and then iterated across the matches to catch each separate word. And, voila, it worked! A fully functional command-line hapax finder.

Then the exciting part—finding texts to feed thru. Project Gutenberg has an archive of public domain books. I downloaded Moby Dick. Beep beep boop boop. A few seconds later, a list of 8,622 hapaxes. Very good algorithm.

Command Line to Web Site¶

Next I knew that I wanted to get this hapax finder working as a website. It was also a good chance to learn to use WebAssembly.

WebAssembly is a type of code that can be run in modern web browsers—it is a low-level assembly-like language with a compact binary format that runs with near-native performance and provides languages such as C/C++, C# and Rust with a compilation target so that they can run on the web. It is also designed to run alongside JavaScript, allowing both to work together.

–[MDN]https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/WebAssembly)

What this means is that you can compile C++ code to WebAssembly, and then run this in the browser from your website. To do this I used Emscripten, an open-source C++ compiler that compiles to WebAssembly. And to use Emscripten, it was time to finally learn CMake.

CMake is the de facto standard for building C++ projects. Like a lot of things in the C++ universe, it's a little arcane and unwieldy. I'd been putting off learning to use it because of this, but it wasn't so bad to get this simple project set up. Now the problem was getting Emscripten to generate WebAssembly that I could run from the browser.

I ran into a string of issues, that I was solving one-by-one, until eventually I got stumped. I could get the WebAssembly version of my hapax code to run when the website was loaded, but I needed to be able to trigger it after a user had uploaded their own text file. I could not figure this out. I read thru all of the Emscripten docs. I generally do not like learning from YouTube videos, but I realized that I what I really needed to see someone using Emscripten and WebAssembly successfully. I watched an hour long grainy video of a man using Emscripten, and there it was: I needed to tell Emscripten that I wanted export the main function, which the docs had strongly suggested was not something one needed to do.

I had the code working on a bare-bones site. You could upload your own text files, and it would generate all the hapaxes. I wanted it to be pretty, so I mocked it up in Figma, did some design iteration, and then coded that up. I still didn't love it, so I showed it to my partner, Abigail, a brilliant graphic designer—she helped me push the design even further.

I included some examples that you can open on the website. These are .txt files of hapaxes from various public domain texts that I've pre-processed, and live on the server. I find it notable, and a testament to WebAssembly's "near-native performance", that reading thru these text files and adding the contents to the site is slower than actually running the hapax finder code yourself from the site.

But so, yes, it works! And it looks nice!

For the Future¶

- Currently can only read plaintext files. I'd like to expand that in the future. There's lots of C++ libraries to help with this.

- I'd like to offer some more sorting/organizing tools for the hapaxes you generate. E.g. arrange hapaxes by word-length.

- The hapax finder could be p easily expanded to be a word-frequency finder. I'd love to set up a site that generates nice word-frequency graphs and charts.